Time for reality check on State’s capacity to build social housing

One interpretation of the 2020 general election result and Sinn Féin’s subsequent rise in opinion polls is that the electorate is now increasingly left leaning. Some argue there is latent demand for a European social-democratic model with a greater role for the State in providing public services, infrastructure and specifically housing.

This is a questionable assertion. Irish voters have not yet had to pay higher income taxes to fund public services and investment. Opposition to property taxes, the universal social charge and water charges are still fresh in the mind. There have been few calls across the political spectrum for broad-based tax rises to fund an expansion of the State.

Nonetheless, there have been enormous rises in expenditure. Core health spending in 2022 is expected to be €21 billion, up 34 per cent on 2018.

Time and again the fiscal position has been bailed out by buoyant corporation taxes, so difficult choices on personal taxation have been avoided. How long can this nirvana persist?

There are certainly risks to the potentially unstable corporate tax base. It is also unclear if the Government’s many commitments can be met within the envelope set out in Budget 2022. These include the Climate Action Plan, Sláintecare and the sustained high level of public capital investment set out in the National Development Plan and the Housing for All strategies.

Gross public investment spending is planned to rise from €8.8 billion in 2020 to €13.3 billion by 2023, equivalent to 5 per cent of gross national income. These plans should automatically raise concerns about the ability of the State to secure value for money and invest wisely.

In November, the Irish Fiscal Advisory Council (IFAC) set out its view. First, when capacity pressures are emerging, particularly in construction, the council argued fiscal policy should arguably “lean against the wind”, taking some of the heat out of the economy.

Poor record

Second, Ireland has had a poor record in managing large public investments, The IFAC’s report outlined a catalogue of spending over-runs: the National Broadband Plan (up 440 per cent); National Children’s Hospital (up 135 per cent); the first construction phase of the Luas Line (up 289 per cent); and Dublin Port Tunnel (up 160 per cent).

House completions

Can these problems be avoided in the future? The IFAC noted the Department of Expenditure and Reform has itself said its ability to scrutinise costings of capital investment, assess feasibility of delivery plans and procurement needs to be strengthened.

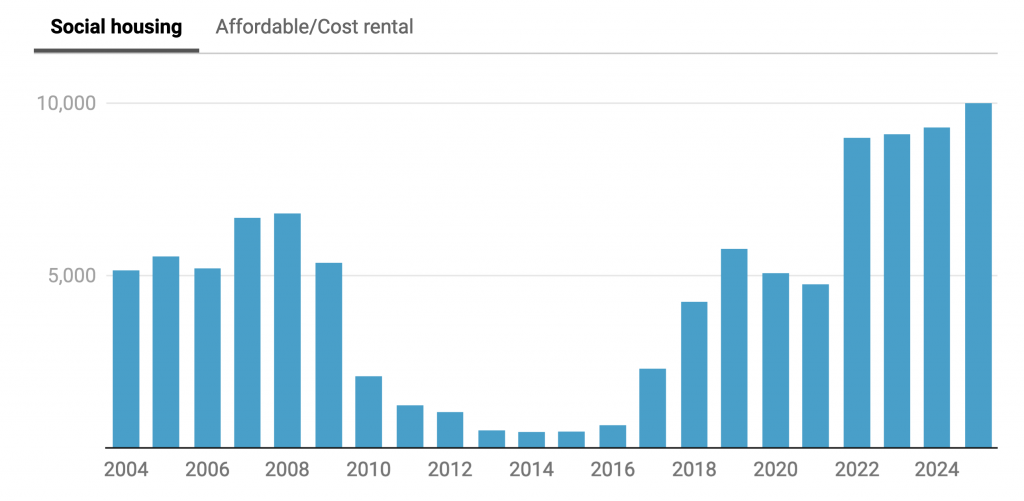

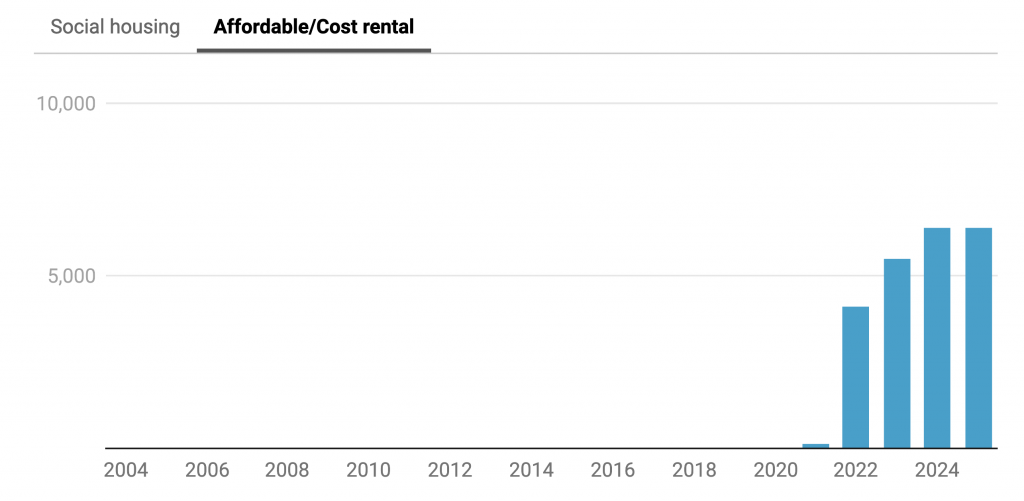

Housing for All is intended to be the largest programme of social housing construction in the history of the State – expected to deliver 90,000 homes by 2030. Perhaps not fully appreciated is how ambitious the targets are in the near-term. Funding has been secured for 13,000 units in 2022, 9,000 social houses and 4,000 affordable/cost-rental homes.

Budget 2021 provided more than €2 billion of funding for 9,500 social housing units to be built last year, but just 3,144 were completed in the first nine months

The plan is to more than double output from the 5,000 social housing units completed in 2021.

Budget 2021 provided more than €2 billion of funding for 9,500 social housing units to be built last year, but just 3,144 were completed in the first nine months. Of course, the Covid-19 pandemic may have delayed activity. Nonetheless, it seems highly unlikely output will rise anywhere close to the 13,000-unit target set for 2022 and doing so in 2023 will be extremely challenging.

Setting the bar high may help exert political pressure for delivery. Housing for All also contained other initiatives, such as the equity loan scheme and measures to expedite planning processes, that may help private sector homebuilding.

However, there has been little discussion on whether Approved Housing Bodies (AHBs), the Land Development Agency and local authorities can scale up social-affordable housing delivery effectively.

For the city council, each new project requires an open tender process so there is no ability for it to bargain on price and exploit economies of scale

There are certainly reasons for concern. Speaking in late 2020, Brendan Kenny, former deputy chief executive of Dublin City Council, drew attention to worrying features of the procurement process for social housing projects that drive up costs.

Open tender

Private developers can build long-term relationships with contractors, offering multiple sequential projects to negotiate down on price. However, for the city council, each new project requires an open tender process so there is no ability for it to bargain on price and exploit economies of scale.

This was one reason put forward by Kenny to explain why the average build cost, excluding land, of 461 social housing units built by Dublin City Council across seven schemes was an enormous €429,000.

In addition, Kenny argued the level of oversight by the council on social housing projects had limited the pool of contractors tendering. Finally, opposition to social housing is the norm, necessitating lengthy pre-planning consultation and leading to delays and even legal challenges.

A broader issue is capacity within the construction sector itself. The IFAC has estimated employment in construction will have to rise to 180,000 to deliver the public capital programme, up from 144,000 currently – but with labour shortages already a growing problem. Meanwhile, supply-chain issues have contributed to a marked pick-up in input costs for construction sector firms.

Many commentators argue the State should just build houses – as if this exercise were as simple as flicking a switch. However, the challenge is no longer funding, but delivery. A realistic discussion on the capacity of the State, approved housing bodies and local authorities to do so and in a cost-effective manner is long overdue.

Source Irish Times